German is no stranger to unique words that describe very particular emotions or concepts. What other languages require full sentences to convey, German can easily communicate in a single word. Such words give German a certain dramatic flair that its counterparts can only dream of.

Many of those words are formed by combining pre-existing ones. This is not a unique feature of German, as other languages create new words similarly. Look no further than brainstorm, aftermath, or lifeboat in English, or gratte-ciel, lave-linge or amuse-bouche in French.

What differentiates those languages from German is perhaps the lack of emotional weight carried by their creations. Whenever I come across Weltschmerz, Zeitgeist or Kopfkino, my mind wanders into territories not invoked by newspaper or porte-chapeau.

Whereas German relied more heavily on combining its pre-existing words, English and French tried to add some oomph to their vocabulary by borrowing Greek and Latin prefixes, suffixes and roots. This phenomenon left us with gems such as utopia, telepathy, or claustrophobia. To be fair, at some point the German word wizardry ran out of steam and spewed dubious results like Zahnfleisch, Tintenfisch or Faultier.

Tooth flesh, ink fish and lazy animal aside, let’s dive into two beautiful German creations: Wanderlust and Fernweh.

Hiking as a national obsession

When Germans are not busy coining new words, they’re hitting the 200,000-kilometre network of hiking trails that Germany offers. Like word creation, hiking packs an emotional and philosophical punch that transcends the physical.

Founded in 1883, the German Hiking association is among the oldest in the world. It counts over 500,000 members across various regional hiking clubs. The association helps maintain the trails, conserve the environment and train hiking leaders. This goes in line with the proliferation of clubs in Germany, where almost every hobby or interest, no matter how outlandish, can find a home.

Germany’s geography also plays a role in promoting hiking as a national activity. Vast swathes of flat land make hiking accessible to almost anyone, while the mountainous terrains of the Alps and the Harz cater to those looking for a challenge.

Are we out of the woods?

Another factor to consider is the abundance of forests and the role they played in shaping the German psyche.

In Roman times, the Germanic tribes were seen as nothing more than barbarians living in forests. Those tribes had the last laugh when they defeated the Romans in the battle of the Teutoberg Forest.

As the Brothers Grimm started collecting German folk tales, a forest often took centre stage in their writings. Iconic stories such as Red riding hood, Snow white and Rapunzel epitomise the role of the forest as both a setting and a symbol. The poorly-lit innards of a forest heighten the mystery and threat while accentuating the character’s growth in overcoming the perils.

In his book Der Deutsche Wald, Detlev Arens highlights the political role of forests in forming the German identity and later in building a German nationalism. Germany chose to distance itself from its arch-enemy France, and forests clearly showcased this contrast. Germans proudly boasted their attachment to the forest and by extension to their ancestors, the forest-dwelling tribes, and Nature in general. On the flip side, the French had long forgotten about their roots and preferred to embrace parks, a man-made contraption detached from the pristine qualities of a German forest.

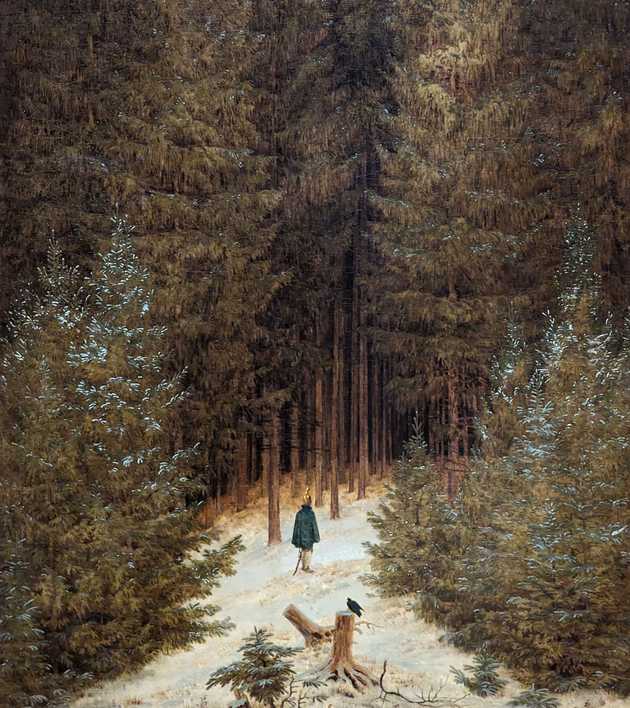

Caspar David Friedrich’s Der Chasseur im Walde shows a German forest engulfing a lonely French soldier.

Caspar David Friedrich’s Der Chasseur im Walde shows a German forest engulfing a lonely French soldier.

German romanticism and the desire to wander

Romanticism emerged as a current of thought in what later became Germany during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It promoted a return to simpler times, favoured the countryside over city life, and touted a communion with nature.

The rise of Romanticism can be understood as a reaction to the ideals of the Enlightenment. Instead of reason, science and social progress, the romanticists sided with emotions, nature, and individualism.

What better way to be alone in nature and examine one’s emotions than to hike. This yearning to wander came to be embodied in Wanderlust. Word for word, Wanderlust means a desire to wander, to hike. The term gained prominence through the works of romanticist authors, who used in their poems and songs. The essence of Wanderlust can also be seen in many paintings of the era.

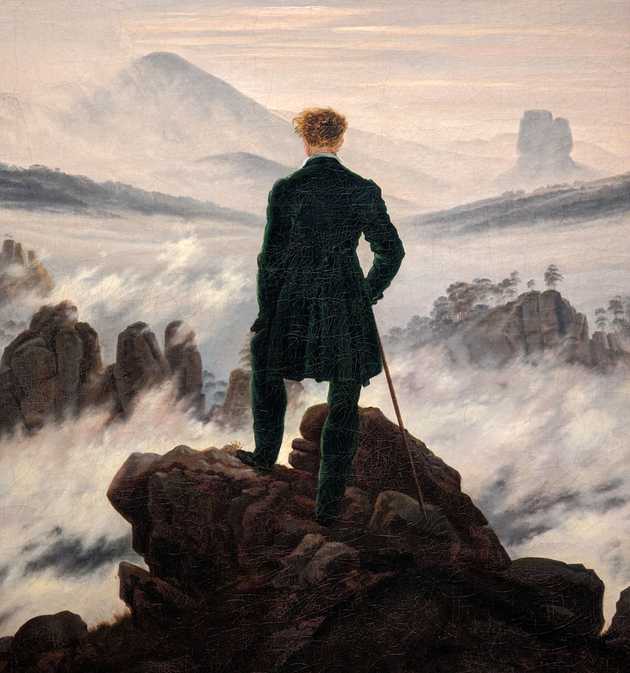

Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer by Caspar David Friedrich is one of the most famous paintings of the Romanticism era

Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer by Caspar David Friedrich is one of the most famous paintings of the Romanticism era

This pain is far from over

Picture this. You’re stuck in a 9-to-5 job you hate. You no longer can tell weekdays apart. Your brain is running on coffee and online cat videos. All you can dream about is to get away from it all, to a place you can’t even remember the name of, let alone pronounce correctly. Well, German got you covered. Introducing Fernweh!

During one of those endless meetings that could have been an email, you decide to do something useful for once and look Fernweh up. Some pretentious language blog cough cough tells you it’s one of those mystically untranslatable German words. The blogger explains that it literally means ‘far pain’. Furthermore, it’s said that the term was coined by Prince Hermann Ludwig Heinrich von Pückler-Muskau who used it in many of his travel journals in the 1830s. Rumour has it that he created it as an analogue for Heimweh, homesickness (lit. ‘home pain’). As the blogger rambles on about hiking, forests and romanticism, the only question crossing your mind would be: “Did Prince Hermann Ludwig Heinrich von Pückler-Muskau travel so much to forget how long his name was?”

When you walk into the nearest tattoo studio to get Fernweh inked on your forearm, you can tell the artist all about it. You proudly explain that Fernweh conveys a yearning for far-off places, away from one’s familiar surroundings. You even mention this quote you came across on the Deutsche Welle website: “One recovers from Fernweh once homesickness hits, and vice versa”.

Mixing pain with pleasure

The difference between Wanderlust and Fernweh is painfully obvious. It’s a tale of Lust vs. Weh, of desire against ache.

The nuance lies primarily in the emotional tone and focus of the longing. Fernweh highlights the destinations, specifically those that are distant and unknown, and carries a more poignant, sometimes melancholic desire. Wanderlust, in contrast, emphasises the act of travelling and exploring itself, with a more positive, adventurous connotation.

Speaking of distant destinations, it’s time for the USA to intervene and usher in a plot twist.

When words wander onto other languages

Back at the tattoo studio, the buzz of the needle pulls you into a trance. You daydream about the immaculate sandy beaches you will trample on and the locals who will feign friendliness for some of your hard-earned cash. Feeling on top of the world, like the wanderer in Caspar David Friedrich’s famous painting, nothing can shake your presumed confidence.

That is, until the tattoo artist nonchalantly asks you, “You say Fernweh is untranslatable, but isn’t it basically wanderlust in English?”. Unsure what hurts more, the needle or this uncalled-for question, you realise that getting that tattoo was a bad idea after all. Alas, it’s too late now, and you don’t want to show up at the office on Monday with Fer on your forearm, do you?

The tattoo artist is actually right. Wanderlust, itself an untranslatable German word, is the closest alternative for Fernweh in English. Its first recorded usage is in the American archaeologist and historian Daniel G. Brinton’s 1902 book The Basis of Social Relations: A Study in Ethnic Psychology.

[…]the goading restlessness which has driven single tribes or groups of tribes into aimless roving. This Wanderlust arises as an emotional epidemic, not by a process of reasoning. It drives communities from fixed seats and comfortable homes, transforming them into migratory and warring hordes.

Hashtag wanderlust

At the time of writing, #wanderlust is used in over 150 millions post on Instagram. The rise of social media and the proliferation of travel content breathed a new life into wanderlust.

The desire to wander is no longer in search for answers to existential questions. It is a call for likes, shares, and user engagement. Travel has become a career path, pseudo-identity and a cry for social validation. In a day and age where cheap flight tickets are flying off the shelves and English has broken down the communication barriers even in the most remote places, travelling is no longer a luxury reserved to a few, but a commodity consumed by many. It is no longer about seeing the world, but being seen by it.

Digital nomads, today’s perpetual wanderers, boast about their unique lifestyle on idyllic islands, in nations half of us didn’t even know existed, to make the rest of us regret our responsible adult decisions. Who doesn’t want to run their online pyramid scheme business from a beach? You thought cleaning the sand off your feet was difficult after taking a dip? Good luck cleaning that laptop!

Outside some uncontacted tribes and the depths of the ocean, our planet has been thoroughly explored, mapped and studied. There are no truly remote places any more waiting to be discovered and sketched à la Humboldt. That’s why perhaps our longing for far-off places is taking us beyond planet Earth. I see intergalactic wanderers in the stars.

Just as German gave English the closest synonym to one of its untranslatable beautiful words, the Internet repackaged it into yet another hashtag.